Shell Collecting With a Vengeance: Ocean's Impact on Ordnance

Gene L. Fabian

Test Officer, Threat Detection & Systems Survivability Branch, Survivability/Lethality Directorate

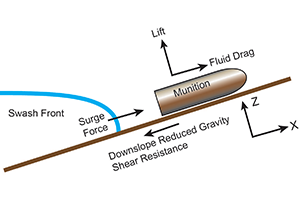

Schematic of the forces acting on a munition on a beach face.

World War II military ordnance has washed up on the beaches of several U.S. coastline states. Soil erosion on mid-Atlantic beaches exacerbates the problem of munitions washing up on beaches. ATC is testing to find the safest ways to recover ordnance from our coastlines.

Bombshells on the beach typically donít carry sinister connotations as vacationers escape the summer heat at nearby shores. However, one does not need to dig deep on the Internet to find reports of unexploded military ordnance routinely washing up on beaches along the East Coast.

Given recent environmental considerations, the idea of offshore disposal of excess military ordnance is perplexing, but the practice was authorized between 1919 and 1970. In 1972, the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act was signed into law, and cleanup has been prioritized. Since then, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has identified hundreds of locations within formerly used defense sites that contain discarded military munitions and unexploded ordnance, known as UXO, in the underwater environment. Live artillery shells, projectiles, bombs, mines and grenades more than 70 years old have been recovered, posing the risk to the public of UXO detonation or exposure to toxic chemical agents.

Recovery of underwater munitions, however, can be even more dangerous than leaving them in place, as many have deteriorated from long-term exposure to the elements. ATC is supporting a research team from the University of Delaware Center for Applied Coastal Research (UD-CACR), led by Dr. Jack Puleo, on an unprecedented project to determine the impact of ocean water movement (velocity, shear stress, turbulence and surge) on munitions movement (burial, exposure, transport) on the beach faceóthe sloped portion exposed to the swash of waves.

The size, shape and weight of munitions also affect mobility. Several surrogate and inert munitions of varying sizes and shapes will be tested. The research team will take detailed, time-series measurements of wave forcing and movement on the beach face in the swash zoneóthe beach area that is intermittently submerged. Technologies such as overhead, side-looking and submerged camera imagery; GPS; ultra-wideband surveys; and current meters will be used. The study results will provide more information on the hydrodynamic forces that control munitions movement and on the safest ways to remove or neutralize the unexploded ordnance.

ATCís Littoral Warfare Environment outdoor wave flume will be the site of initial pilot testing under low- and high-energy wave conditions. Afterward, UD-CACR researchers will perform tests under the same wave conditions on shallow and steep sloping beaches in Delaware and New Jersey. The study group will use the data to determine which factors control the fate of discarded munitions and UXO on the beach face: Will they become buried or unburied? Will they transport or remain fixed in place? Ultimately, the results will help restore public safety along coastal areas burdened with discarded military ordnance.

You are now leaving www.atc.army.mil and entering another site. You will automatically be forwarded to the target page within five seconds.